As we near the beginning of a new school year, it’s time to reflect on the effects distance learning has had on our students. Most of the feedback I’ve heard—whether in person or read online—focuses on the negative effects of this experience; how students missed a whole year of schooling due to ineffective practices of distance learning.

Surprisingly, an article published in the Washington Post titled Growing up on screens: How a year lived online has changed our children doesn’t completely discredit the experience, and even highlights some of its positives. In the article, Ann Masten, a professor of child development at the University of Minnesota who studies risk and resilience in children, describes the duality:

“Screens aren’t inherently good or bad, but it’s what they’re being used for and what they are replacing that matters. In the past year screens have made things possible, like education and communication, that have been important for getting people through a period of isolation.”

When the pandemic started, we began relying extensively on communicating via Zoom to conduct business and visit with family and friends. But the larger the number of participants, the more unbearable the experience can become, especially when it comes to discussions where everyone wants to weigh in. People are so eager to be heard that they’re talking simultaneously, interrupting each other and making you wonder if you even want to take part in them. Of course, these experiences aren’t always negative, as I explained above. Just being able to see friends and family, which would’ve been impossible otherwise, is a great comfort.

When Zoom is used for learning, the biggest problem is that it leads to passive learning. The role of teacher as “sage on the stage” and student as passive listeners becomes even more pronounced. To avoid talking over each other, students stay silent during instruction. As you can imagine, it’s not long before they become bored and their minds begin to wander. This is what led one teacher to reach out to us about implementing project-based learning in her school. She was struggling to keep her students engaged with online learning, and she was not the first one to tell us that.

By the beginning of the 20th century, educational philosopher and psychologist John Dewey had already realized that when working on projects, students are much more interested and engaged, and therefore learning is more effective. Since then, a plethora of research has validated that same reality. If project-based learning had been applied during the pandemic instead of traditional teaching methods, it may have produced far different results in terms of student engagement and knowledge gain. In fact, when project-based learning is performed virtually and implemented in real-time on a collaborative platform, it brings to life a dynamic atmosphere where students see classmates present with them through their contributions.

Take, for instance, the United Independent School District in Texas, whose students exceeded expectations during distance learning due to early adoption of project-based learning. Their 4th and 5th grade students completed a variety of complex projects, ranging from tackling tasks from the Texas Performance Standards Project, to unique projects created by the students catered to their own interests. Purposeful, engaged learning is evident in every stage of their projects, which explored everything from animal habitats and gaming tech to the history of Mexican food and garden design.

But, for project-based learning to be a successful experience that engages student interest, it requires a substantial investment of time and effort by the teacher. In addition to a very detailed project design and preparation of multiple project assets, teachers must also understand project-management and how to implement it in their classes. Students need to be assigned roles with clearly defined tasks, leading them to a realization that the project’s integrity depends on their level of contribution. The project must also be meaningful to the students and positively impact society in some way.

While this extra planning may feel overwhelming for teachers at first, it’s essential for ensuring their application of project-based learning is successful. And research supports that these extra efforts will be rewarded by positive learning outcomes. In a study published in February by the George Lucas Educational Foundation in collaboration with five universities, they found that students in project-based learning (PBL) classrooms across the United States significantly outperform students in typical classrooms. Kristin De Vivo from Lucas Education Research states “the evidence is clear, rigorous PBL results in a significant boost in academic achievement for students from many different backgrounds.”

The mention of the word ‘rigorous’ is not accidental—it points to the fact that in addition to higher expectations from students, the load on teachers is substantial as well. In the same announcement, Linda Darling-Hammond, president of the California State Board of Education and Professor of Education, Emeritus at Stanford is quoted as saying:

“These results demonstrate that well designed experiences with PBL … can boost engagement and learning achievement“

Again, the words ‘well designed’ are there to make clear that these exceptional outcomes will only come with substantial preparation by all stakeholders.

Improved student achievement isn’t the only advantage of project-based learning. Students actually enjoy being part of such projects, especially when they are well designed and managed.

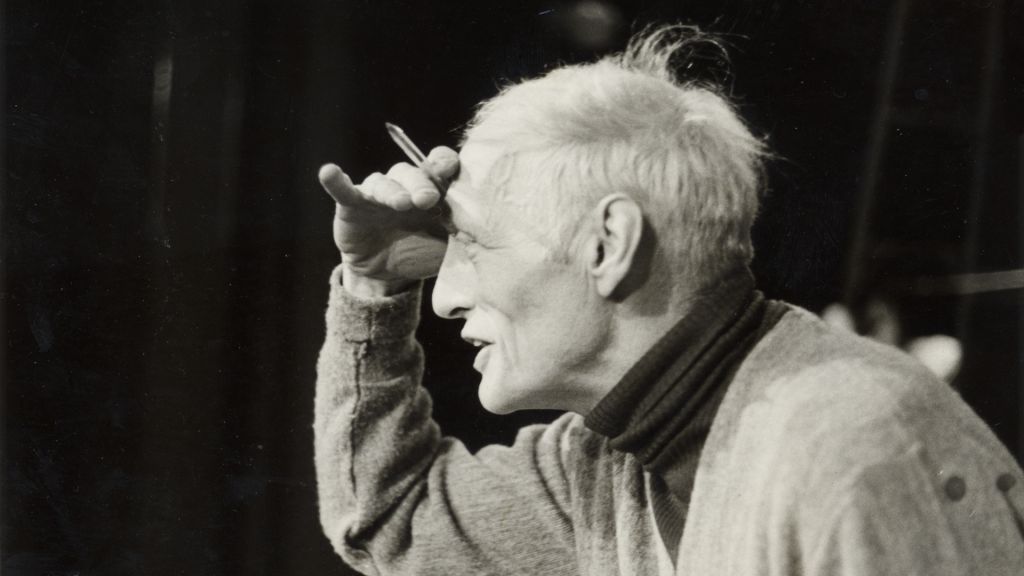

One teacher that proved that point was Albert Cullum, an educator in New York from 1956 to 1966 who had an intuitive sense of what works in education. Cullum regularly incorporated progressive teaching methods, like project-based and social emotional learning, into his fifth grade classroom.

A 2005 documentary titled A Touch of Greatness featured on PBS reunited Mr. Cullum with his previous students, who said that they loved the way he taught them so much that they wouldn’t miss any day of school for the world. Reflecting on the experience, Cullum notes:

“We must remember how children learn rather than how we teach, through movement, through emotions, through activities, through projects, all the basics fit in and they’re learning without realizing they’re learning. Learning’s not painful, learning should be joyful.“

Students love to be part of authentic projects where they’re part of a team effort, and their contributions are crucial for completing the goal. Projects of this nature were part of the George Lucas Education Foundation studies, where students answered questions like “What is the proper role of government in democracy?” by coordinating a presidential campaign, taking on the roles of the candidates, lobbyists, and media; or where students explored sustainability by conducting a personal environmental impact audit and developing a proposal to reduce consumption.

The experience and outcome of online learning could’ve been different if our educational institutions had opted for more engaging forms of instruction, instead of attempting to deliver the same traditional teaching practices found in the classroom. Planning some PBL experiences would’ve paid dividends in terms of student engagement and achievement. And while it would’ve required more preparation on the front end from teachers, when we consider the loss of a year’s worth of learning, the effort would’ve been worth taking.

From here, we can only hope that our educational institutions realize that the time of traditional teacher-centered instruction is over, and that COVID becomes a catalyst for adopting innovative, research-based practices like PBL. Providing teachers with essential training in project design and management is a worthy investment when it results in a more collaborative and academically accomplished classroom.